As I come to the end of my 7th year as Department Chair, I can’t help but reflect on the ups and downs of my time so far. I wrote about the lessons I learned in my first year as Department chair and it’s fun to look back at that, but whoa… was there a learning curve! At that time, I commented on how much I learned, and how much I have yet to learn. I still believe that I have a lot to learn, but I also feel that I have a lot more to offer now.

My School has two new Department chairs starting this fall, and I’ve been thinking about what advice I might give them as they embark on their new adventure, and what advice might have been helpful for me 7 years ago. With these thoughts in mind, I put together my Department Chair Survival Guide. Coincidentally, there are 7 points. I’m not saying that I only learned 1 thing each year, but if you watch enough NCIS (and I’m addicted to it), you know that there’s no such thing as a coincidence.

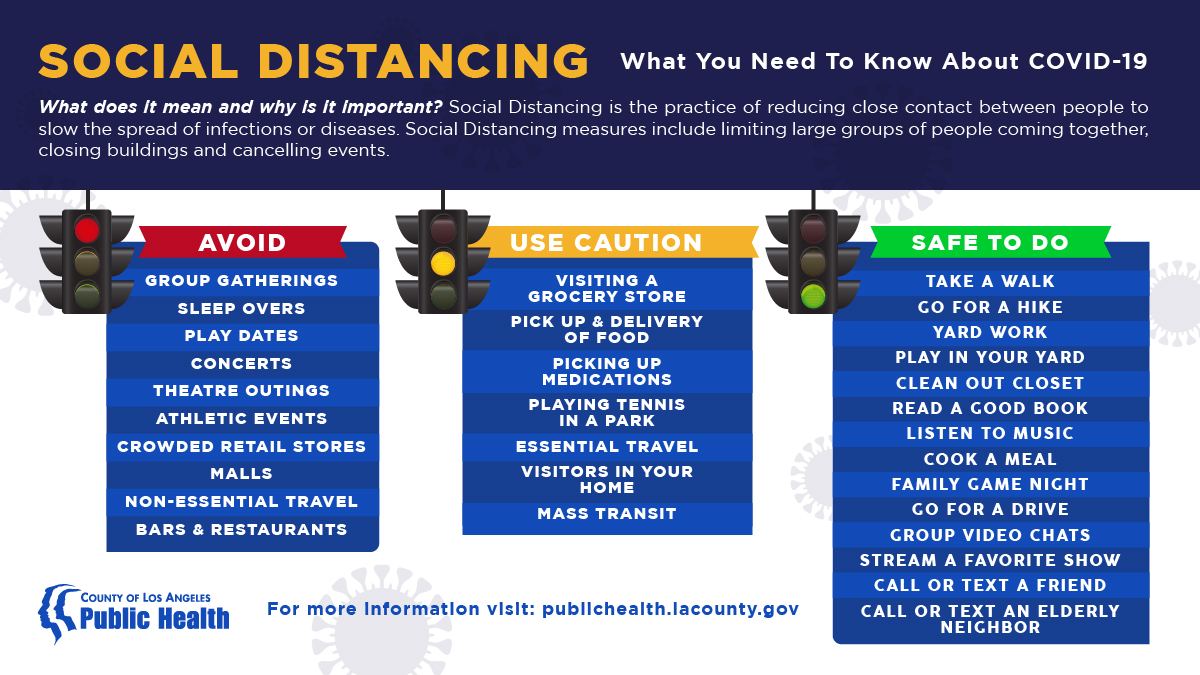

#1: Don’t let a pandemic break out.

OK, so this is not necessarily something you can plan for, nor is it within your control. But my job COMPLETELY changed when the COVID-19 outbreak occurred. Everything changed in March 2020. Most challenging for me was trying to reconcile my desire for my colleagues to, most importantly, look at after their own health and the health of their family. But I also had to ask my colleagues to do more – change how they were teaching, perhaps when they were teaching, how they engaged with each other… everything was different. Frankly, so much changed that was out of my control, and I think that I suffered tremendously from that lack of control.

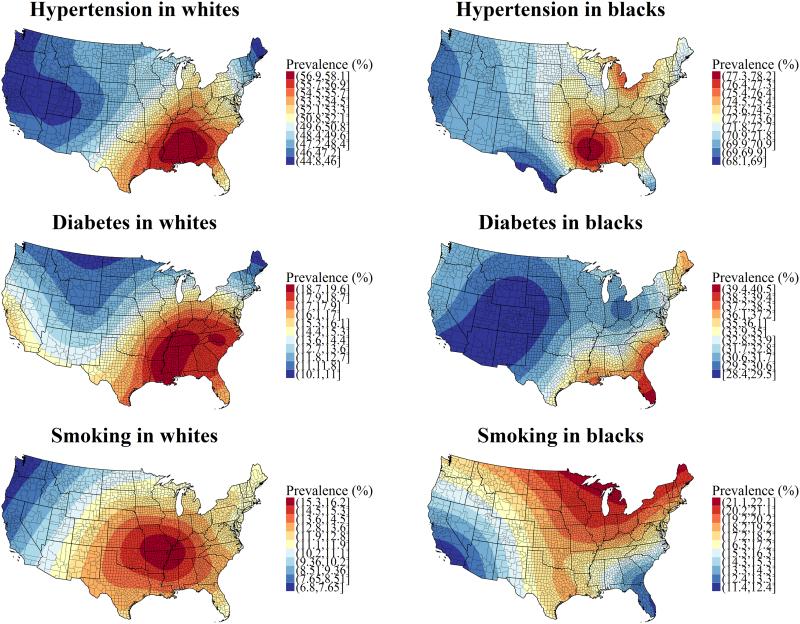

There were some positives, though. For example, I chair a Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, and where better to be during a pandemic? I am surrounded by smart people, many of whom study just this thing! It was my distinct pleasure to see my colleagues, particularly my junior colleagues, quoted in the media, working with health departments (locally and internationally), and helping to guide response at our institution.

#2: Have (and retain) fantastic faculty.

I am so honored to work with faculty who enjoy doing their jobs (most of the time). They love teaching and mentoring students. They are curious folks who are excited to learn new things. They are truly invested in making our Department better. Working with faculty who are fantastic really makes my job easier. Now, I was fortunate to inherit great faculty when I came to my institution, but we also worked together to ensure that we hired great faculty who share our desire to train outstanding students, who are asking important research questions, and who want to continue to build an amazing Department. And we have worked hard to create a culture and environment that faculty do not want to leave.

#3: Have (and retain) amazing staff.

Faculty alone don’t make a Department, and I’d argue that amazing staff are even more important to a Department’s success. And the staff in my Department are AH-MAY-ZING! The staff are the first line of defense for almost everyone who comes through the door, they have institutional knowledge, and they know “who to know” at your University. Frankly, on a day-to-day basis, the staff are the people I interact with most, and I am so lucky to work with such great staff. Anyone who knows me knows that they better not fuck with the staff. I will take their side every day of the week (and often do).

#4: Assess and refresh regularly.

When you’re in the same job for a long time, it’s easy to get stale. I’m about to do annual reviews for the 8th time, for example. But it’s not just annual reviews, it’s the 8th time I’m going to do a lot of things! And as I’ve aged, so have the members of my Department (except for the students – they continue to stay the same ages year after year!). So, I regularly assess what I’m doing and how I can do it differently, not only for my own sanity, but also so that I can make sure that I’m doing all I can to ensure the members of my Department have opportunities for success. Changing the way things are done from time-to-time isn’t always easy, and isn’t always well-received, but doing so provides opportunities for leaders to emerge in the Department and for people to learn new skills, and creates opportunities for me to see things in a new way. It also keeps my job from being boring and helps me to be excited about my job. And being a chair is definitely a labor of love, so without excitement for the job, it can be a slog. A major slog.

#5: Have a support network.

There’s a saying that: “It’s lonely at the top.” While being a Department Chair isn’t quite “at the top,” it is a leadership role, and it can definitely be lonely. I work with the best people, but at the end of the day, I do their annual reviews. When issues arise, they often arise among their colleagues, and it isn’t appropriate (or fair) to share those. So it is important to have a network to rely on for support, to vent to, and to laugh with. It is also helpful if these are people you can share a meal or a beer with, and even better if you can share a meal AND a beer. For me, my support network includes other chairs (both locally and within my field), as well as other academic leaders at my institution and elsewhere. My School has only 4 departments, so our group of chairs is small and close-knit – we work together a lot and experience many similar challenges. But some of the challenges are different, and it is great to be able to reach out to other Biostatistics or Epidemiology chairs when discipline-specific issues arise. I’ve also never been afraid to reach out to others to ask for help and have developed great relationships with some mentors in that way. I feel very fortunate to have so many people to turn to… leadership definitely has not been lonely for me.

#6: Relatedly, have a life outside of work.

And just as it is important to have an academic support system, it is important to have a life outside of work. Oh, and to prioritize this so-called “life.” I am so fortunate to have a family that I love, hobbies that I enjoy (although my husband likes to remind me that watching TV is not a hobby, ahem – NCIS is definitely a hobby), and friends who I spend time with. Over the last 3 years, I have decided to prioritize my health and fitness, to the extent that I occasionally rearrange my meetings to accommodate my training schedule. This is not only a way to stay physically healthy but also a way to stay mentally healthy. Don’t get me wrong. I work a lot. A lot a lot. But I wouldn’t enjoy my work without something else to sustain me. I take vacations. Real vacations, where I don’t even check my email. I take weekends off. I do things to restore my energy so that I’m ready for work.

#7: Remember why you’re doing the job you’re doing.

I think it is easy to lose sight of why we serve in the roles we serve in (regardless of the role). We get so caught up in the day-to-day of our jobs, we forget what motivated us to choose our professions. I sought out my role as Department chair for many reasons. First and foremost, I see my role as a service to others, and through my position, I seek to make their lives better, their successes greater, their joy happier. This is a tall order, and it is what continues to motivate me after 7 years: my desire to help other people be successful. This is true for students, faculty, and staff. And as I’ve grown over the last 7 years, I’ve found other reasons that it is important to do my job well. I’ve seen amazing leadership emerge from among the members of my Department, and I’ve realized that I have an opportunity and a responsibility to provide mechanisms for growth and leadership for my colleagues. Further, in my role as Chair, I can influence the academic opportunities for our trainees through adding new academic programs and critically reviewing our existing ones, and it is important to me that we do so. I’m excited about the changes we’ve made, and continue to make, to ensure that we are providing the best education to our students. I have personal reasons I enjoy being Chair, as well – primarily among them is that I am presented with new challenges every day, forcing me to constantly learn and try new things. And as an academic, what is better than a job that allows me to continually learn?

The job of Department Chair is not easy and is often referred to the as “middle management” and sometimes called the most difficult role in academia, due to being sandwiched between the Dean and the Department. Despite the challenges, these last 7 years as Department chair have been the most rewarding of my career and I’m excited about the years to come.

but it wasn’t very common among my peers. I was fortunate to have two classmates who were also expecting around the time that I was – one had graduated before her baby was born, the other never finished her PhD. Data on completion rates among doctoral students who become pregnant are hard to come by, but

but it wasn’t very common among my peers. I was fortunate to have two classmates who were also expecting around the time that I was – one had graduated before her baby was born, the other never finished her PhD. Data on completion rates among doctoral students who become pregnant are hard to come by, but

wondering if I was ever going to shower regularly again. And on the other days, we spent so much time getting back up to speed on our dissertations, progress was slow. After 4 months, we put her in daycare 3 days a week. This gave us each more time at work, and also gave us each a day alone at home with our daughter, but was also costly. We were so lucky that the University of Michigan provided a childcare subsidy for graduate students at that time (

wondering if I was ever going to shower regularly again. And on the other days, we spent so much time getting back up to speed on our dissertations, progress was slow. After 4 months, we put her in daycare 3 days a week. This gave us each more time at work, and also gave us each a day alone at home with our daughter, but was also costly. We were so lucky that the University of Michigan provided a childcare subsidy for graduate students at that time (

Did I mention I met a

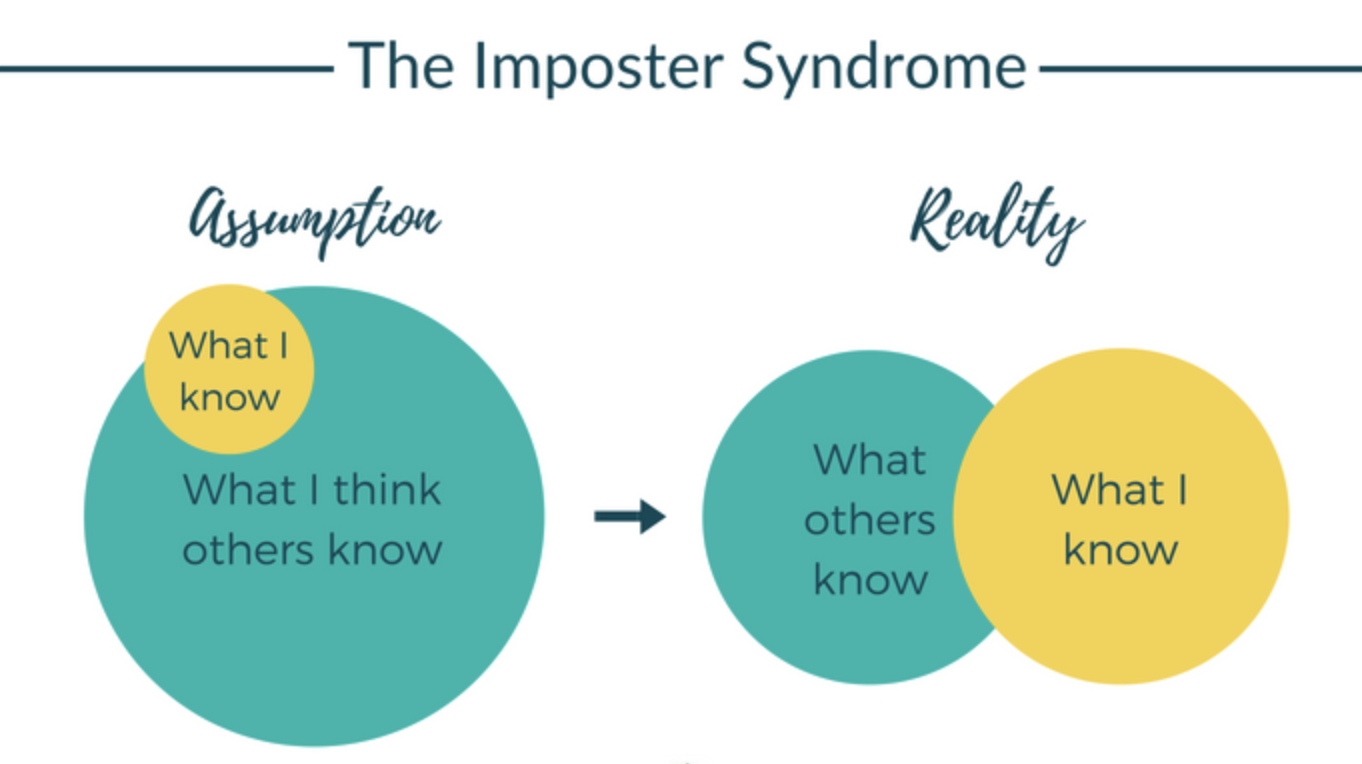

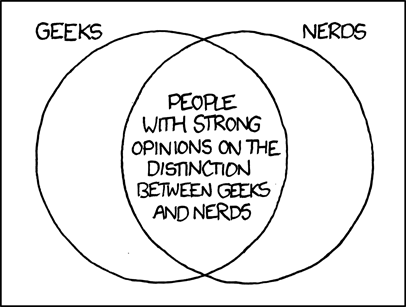

Did I mention I met a  Not a lot of data exist about imposter syndrome in academics, although there are a lot of stories and blogposts discussing it. What research is out there suggests that imposter syndrome tends to occur more frequently among high-achieving people, and there is some evidence that black students experiencing imposter syndrome also have higher incidence of anxiety and depression (

Not a lot of data exist about imposter syndrome in academics, although there are a lot of stories and blogposts discussing it. What research is out there suggests that imposter syndrome tends to occur more frequently among high-achieving people, and there is some evidence that black students experiencing imposter syndrome also have higher incidence of anxiety and depression ( While I’m extremely honored that others believe that my experiences can help contribute to their success, and again, I almost always say yes, in the back of my mind, I’m thinking “Why aren’t they asking me about my research? Maybe my research isn’t good enough?” I’m often quick to point out that I’m still quite research active, as if I feel like I need to continually prove myself because after all, isn’t your academic worth judged by the amount of grant funding you have? Yet when I speak to others, I emphasize that success is not one-size-fits-all. Imposter syndrome lives on.

While I’m extremely honored that others believe that my experiences can help contribute to their success, and again, I almost always say yes, in the back of my mind, I’m thinking “Why aren’t they asking me about my research? Maybe my research isn’t good enough?” I’m often quick to point out that I’m still quite research active, as if I feel like I need to continually prove myself because after all, isn’t your academic worth judged by the amount of grant funding you have? Yet when I speak to others, I emphasize that success is not one-size-fits-all. Imposter syndrome lives on.

Almost daily, new articles were being written about instances of sexual misconduct and gender discrimination in science, medicine and academics. Organizations rushed to develop conduct policies that far improved upon what they had, some in very proactive ways, others very reactively. As the Task Force tried to collect information about “best practices” for conduct policies, we had a hard time keeping up! Even now, nearly a year later, the amount of information still coming out can be overwhelming.

Almost daily, new articles were being written about instances of sexual misconduct and gender discrimination in science, medicine and academics. Organizations rushed to develop conduct policies that far improved upon what they had, some in very proactive ways, others very reactively. As the Task Force tried to collect information about “best practices” for conduct policies, we had a hard time keeping up! Even now, nearly a year later, the amount of information still coming out can be overwhelming.

Not all mentoring relationships are created equally. Some are very formal, while others are rather informal. Some are intentional, while others are accidental. Some folks receive mentoring from those “above” them (think Full Professor mentoring an Assistant Professor), while others receive mentoring from their peers, or from those more junior than they are. There is no single approach to mentoring, and most people have some combination of mentors. In fact, often, you may have a mentor that you don’t even realize is mentoring you! Conversely, you may view someone as a mentor who may not view themselves that way.

Not all mentoring relationships are created equally. Some are very formal, while others are rather informal. Some are intentional, while others are accidental. Some folks receive mentoring from those “above” them (think Full Professor mentoring an Assistant Professor), while others receive mentoring from their peers, or from those more junior than they are. There is no single approach to mentoring, and most people have some combination of mentors. In fact, often, you may have a mentor that you don’t even realize is mentoring you! Conversely, you may view someone as a mentor who may not view themselves that way.

their experiences. The attitude of the leaders in my institution (particularly after I was promoted to full professor) was that I was now the mentor, and so why did I need mentoring? I would argue that everyone needs mentorship at every phase of their career, and that mentoring needs change as your roles change, but my argument was met with opposition. It’s hard for me to understand the lack of support for mentoring – seeking out a mentor isn’t a sign of weakness or inability, but rather a recognition that we all need help being successful. We all need folks to help us figure out how to complement our weaknesses, and who can help us emphasize our strengths. I was fortunate that my paths had crossed with people across the country who were happy to give me advice here or there. And while I never had a formal mentor, I again had a lot of resources that I could cobble together to make sure my needs were met.

their experiences. The attitude of the leaders in my institution (particularly after I was promoted to full professor) was that I was now the mentor, and so why did I need mentoring? I would argue that everyone needs mentorship at every phase of their career, and that mentoring needs change as your roles change, but my argument was met with opposition. It’s hard for me to understand the lack of support for mentoring – seeking out a mentor isn’t a sign of weakness or inability, but rather a recognition that we all need help being successful. We all need folks to help us figure out how to complement our weaknesses, and who can help us emphasize our strengths. I was fortunate that my paths had crossed with people across the country who were happy to give me advice here or there. And while I never had a formal mentor, I again had a lot of resources that I could cobble together to make sure my needs were met. that good). Both were at about the same stage as I, and both were struggling with figuring out next steps, like me. We started meeting monthly for breakfast, finding new places to eat around town, and helping each other see the opportunities and HUMOR in our jobs and in our lives. We laughed so much during those breakfasts, even when we shouldn’t have been laughing, and I believe that without these two colleagues, two friends, I wouldn’t have made it to where I am today. Incidentally, each of us went on to become a Department Chair, and I have no doubt that at some point in the future I’ll see these two again – at Dean’s meetings.

that good). Both were at about the same stage as I, and both were struggling with figuring out next steps, like me. We started meeting monthly for breakfast, finding new places to eat around town, and helping each other see the opportunities and HUMOR in our jobs and in our lives. We laughed so much during those breakfasts, even when we shouldn’t have been laughing, and I believe that without these two colleagues, two friends, I wouldn’t have made it to where I am today. Incidentally, each of us went on to become a Department Chair, and I have no doubt that at some point in the future I’ll see these two again – at Dean’s meetings. And that hasn’t ended now that I’m a Department Chair. A colleague of mine, who was once a Chair and is now a Dean (trained as a statistician) recently asked me about my career goals. She mentioned that she has had the opportunity to help mentor others who are considering applying to Dean positions, and that she’d be happy to mentor me similarly. I emailed her and told her that I’d like to take her up on her offer, and she replied asking me to provide her with a statement of my career goals, as well as my CV. While I am struggling to articulate my career goals (I really love my current job, and am not sure that I’m ready to think about what’s next), I am excited to have the opportunity to have a new mentor, and also to start to explore what future possibilities might be available to me.

And that hasn’t ended now that I’m a Department Chair. A colleague of mine, who was once a Chair and is now a Dean (trained as a statistician) recently asked me about my career goals. She mentioned that she has had the opportunity to help mentor others who are considering applying to Dean positions, and that she’d be happy to mentor me similarly. I emailed her and told her that I’d like to take her up on her offer, and she replied asking me to provide her with a statement of my career goals, as well as my CV. While I am struggling to articulate my career goals (I really love my current job, and am not sure that I’m ready to think about what’s next), I am excited to have the opportunity to have a new mentor, and also to start to explore what future possibilities might be available to me. And as much as I love mentoring, and while I feel responsible for success for all faculty in my Department, I also know that I am not necessarily the best person to mentor everyone. So part of what I negotiated when I started as Chair includes money earmarked for mentoring resources for the faculty in my Department. This money is not restricted to junior faculty, but is available for all faculty should the need arise. Every year when I meet with faculty to discuss their progress, I again offer to help them find mentors (both internal and external), and to provide resources to help foster the mentoring relationship.

And as much as I love mentoring, and while I feel responsible for success for all faculty in my Department, I also know that I am not necessarily the best person to mentor everyone. So part of what I negotiated when I started as Chair includes money earmarked for mentoring resources for the faculty in my Department. This money is not restricted to junior faculty, but is available for all faculty should the need arise. Every year when I meet with faculty to discuss their progress, I again offer to help them find mentors (both internal and external), and to provide resources to help foster the mentoring relationship. es to mentoring, and that we will work to ensure all faculty receive the mentoring they need. I hope we will come to understand how we all need a team of mentors to support our success, and that we will all learn to make mentoring a priority. If you are mentoring someone, learn what their goals are, and get to know what they need from a mentor. Help them meet their goals, not yours. If you’re looking for a mentor, don’t be afraid to ask! People genuinely want to help others be successful, and if they tell you no, you don’t want them as a mentor anyway. In the meantime, I will keep doing what I can to help others be successful, and feel extremely fortunate that others are willing to continue do the same for me.

es to mentoring, and that we will work to ensure all faculty receive the mentoring they need. I hope we will come to understand how we all need a team of mentors to support our success, and that we will all learn to make mentoring a priority. If you are mentoring someone, learn what their goals are, and get to know what they need from a mentor. Help them meet their goals, not yours. If you’re looking for a mentor, don’t be afraid to ask! People genuinely want to help others be successful, and if they tell you no, you don’t want them as a mentor anyway. In the meantime, I will keep doing what I can to help others be successful, and feel extremely fortunate that others are willing to continue do the same for me.

I am incredibly proud of my children, who hiked nearly 30 miles over 4 days with heavy packs on, with no showers, sleeping on the ground, eating mostly dehydrated foods, with no whining and complaining, and no arguing, and loving the challenge of the trip.

I am incredibly proud of my children, who hiked nearly 30 miles over 4 days with heavy packs on, with no showers, sleeping on the ground, eating mostly dehydrated foods, with no whining and complaining, and no arguing, and loving the challenge of the trip.